London, Rome, Perugia December 1962 - January 1963

Bob Dylan: Blowing in the Mind 1967 | Brett Whiteley | Don't Look Back 1967 | London 1962 | Masters of War |

1. Introduction

Unlikely as it may seem, the British and American folk revivals of the 1950s and early 1960s were intimately connected. Songs were shared, artists such as Woody Guthrie (1912-1967) were honoured on both sides of the Atlantic, and songwriters, singers and musicologists travelled between North America and Europe to share and learn from one another. The historic British and European origins of white America, and ongoing immigration through the 18th, 19th and 20th centuries, had left the country with a rich folklore tradition, not to forget the strong, though waning influence of traditional American Indian musical forms. The Appalachian region Ritchie family, for example, based much of their music and songwriting on English forms going back to the Medieval period. Post World War II, American musicologists and musicians such as Alan Lomax, Pete Seeger and Ramblin' Jack Elliott made numerous visits to the British Isles, whilst groups including the Irish Clancy Brothers had a decided impact in the United States during the late 1950s and early 1960s, based as they were for a period in New York.

It is not widely known that in the second half of December 1962, the then 21 year old, and largely unknown, American folk singer Bob Dylan travelled outside of his home country for the first time, visiting England and Italy before returning in mid January 1963. During 1961, following his arrival in New York, he had sung: 'Well I wish I was in London / Or some other seaport town' in the traditional song Handsome Molly. Dylan came to England to star as Lenny in the BBC television play Madhouse on Castle Street, though he was also interested in experiencing first-hand the British folk scene, and perhaps having a brief holiday on the Continent thereafter. The play would be Dylan's first official acting role, though it is not something he subsequently talked about in any detail. The month-long engagement on the Continent would also provide an opportunity to catch performances by Black American singer Odetta (1930-2008), who, alongside with Dylan, was part of Albert Grossman's management portfolio.

This initial European excursion would ultimately prove significant in regard to the singer's development as a singer and songwriter, for, according to one knowledgeable commentator - the folksinger Martin Carthy - Dylan was able ‘to soak up almost as much from a single month immersed in the London folk scene as he had from [the previous] two years in New York’ (Heylin 2009). In addition, during this trip, Dylan had his first encounter with Rome’s famous Coliseum, met up with poet Robert Graves, read his first William Burroughs texts, spent time being chaperoned around London by Pop artist Pauline Boty (1938-1966), was briefly represented by future Rolling Stones manager Andrew Loog Oldham, and wrote a number of songs which were included in his breakthrough album The Freewheelin' Bob Dylan, released in May 1963. Six months after the London visit, Bob Dylan was an international star, due in large part to renditions of his original compositions by the folk trio Peter, Paul & Mary - also managed by Grossman. However, to those Londoners Dylan encountered during the cold December and freezing January of 1962/3 he was just a young American folk singer on the rise. They were not to know that, by the time he arrived in their town, he already had more than 2 years experience as a full-time folk singer, soaking up American and traditional songs, with an initial preference to follow in the footsteps of Woody Guthrie. His residence since late January 1962 in Greenwich Village, New York, had honed his performance skills. His innate talent and increasing confidence was such that Dylan was undaunted by the scene he found in England and the major players he met there, and unafraid to confront them on their home turf. This article outlines the circumstances behind Bob Dylan’s initial British and European visit, describing some of the events which took place during that roughly four week period. It brings together a variety of published accounts and audiovisual sources, highlighting a relatively little-known, yet important episode in the life of one of the most enigmatic, and talented, pop culture figures of the 20th and 21st centuries.

---------------

2. Saville’s hunch

|

| Philip Saville |

During the northern Autumn (October-November) of 1962, British television and film director Philip Saville (1930-2016) was in New York working with folk music historian Alan Lomax (1915-2002) on the soundtrack for the television play Dark of the Moon, which Saville had directed for the BBC back in 1956. Amongst its stars was a young Peggy Seeger (b.1935), sister of noted American folksinger Pete Seeger and herself a working musician. At some point during the New York visit Saville was talking to his friend, the English poet W.H. Auden (1907-73), then a resident of West Fourth Street. Auden, also a fan of folk music, suggested to Saville that they visit Tony Pastor’s Downtown club, located at 130 West 3rd Street. Pastor's was popular with the local lesbian and homosexual community at the time - Auden was gay. It opened in 1939 and remained in existence until 1967, by which time the club had, according to one newspaper report, 'become disorderly in that it permitted homosexuals, degenerates and undesirables to be on the license premises and conduct themselves in an offensive and indecent manner' (Betts 2013). Auden took Saville there because Everybody goes there who is anybody. It’s like going to the place up in Liverpool [The Cavern], that place [where] the Beatles were found.

Saville followed Auden’s advice and happened to see Bob Dylan perform at Pastor’s. As no other record survives of Dylan performing there - and Saville saw him there at least twice - the precise date of the first and later encounters are unknown. Saville was immediately struck by the young folk singer and decided he would be suitable for a lead role in the upcoming television play he was to direct for the BBC, entitled Madhouse on Castle Street and written by Jamaican-born actor and playwright Evan Jones (1927-2012). Saville introduced himself to Dylan at this first encounter, such was his excitement at the possibilities on offer. He later recalled:

When I heard Bob play, well, I thought this is too good to be true. If I can get the BBC to agree to it.

As a performer, Dylan had by that stage (circa October-November 1962) acquired a substantial repertoire of traditional blues and folk material which he presented in a unique style reflecting a genuine connection to the work of artists such as Guthrie. He was also on the cusp of an extraordinary period of writing original material which would culminate in a series of classic albums and performances, both in his home country and on the world stage, from 1963 through to 1966 (Heylin 2009). With this intense activity came international acclaim as a songwriter and poet, plus an unwanted mantle as the voice of his generation. In line with the perceived Woody Guthrie persona, Dylan's early television appearances during 1963-4 reveal a stark, hobo-like, sincere and at times solemn delivery, covering topics such as the brutal treatment of Black Americans at the hands of racists as in The Death of Emmett Till - and the often-harsh life and lonely deaths experienced by ordinary people in that country’s recent history, such as in The Ballad of Hollis Brown. All was not bleak however, for Dylan also displayed a biting wit and youthful humour in life and through performance, especially in some of the songs her wrote reflecting his own life experiences. Saville therefore approached Dylan’s new manager, Albert Grossman, who was supportive of broadening the horizons of his young charge in a similar manner to the singer-film star crossover pioneered by Elvis Presley and carried through by contemporaries such as Johnny Cash, Roy Orbison and Ricky Nelson in the US and Tommy Steele and Cliff Richards in the UK. Dylan considered Saville’s proposal, mindful that he was in the middle of recording an important album and did not want to delay its completion. He was perhaps also influenced in his decision making by an item in the folk music pamphlet Broadside, to which he was a regular contributor. The December 1962 issue included a copy of Dylan’s songs Oxford Town and Paths of Victory, along with the following news item:

Report from Britain: It's hard to imagine the AFL·CIO [American Federation of Labor & Congress of Industrial Organizations] hiring a singer songwriter to tour the nation’s saloons and other places where workers congregate - as the British Trade Union Congress has hired Glasgow's Matt McGinn to tour Britain's pubs and “sing the lads" his songs. In a report on the first leg of his jaunt Matt writes: I have returned from England and the 'Centre 42' Festivals. The Festivals have, I believe, given what will be a terrific boost to the revival in Britain. Some publicans (owners) in whose pubs we sang requested that we somehow make singing in their places a regular feature. In places like Bristol we left a folk song ferment behind us. In Birmingham the existing clubs are recording a terrific increase in membership ...

Dylan knew McGinn, having appeared alongside him and Peter Seeger on 22 September 1962 in a New York Carnegie Hall concert. Dylan and some of his American folk contemporaries were perhaps drawn to the idea of checking out the London scene at this time, in a manner pre-emptive of the so-called British invasion by pop and rock groups including The Beatles, Rolling Stones and Yardbirds less than two years later. The British folk revival of the 1950s and early 1960s had resulted in a proliferation of small folk clubs around the country, with London at its centre. And whilst the focus there was on exposing local tradition and developing new interpretations, there was also a proliferation of recordings and publications by Americans available in Britain, alongside visitations and concert tours. Tony Davis (1930-2017), a British folk singer noted for his time with the Liverpool-based group The Spinners, was then resident in New York, and remembered talking to Dylan around December 1962 about the idea of visiting England:

|

| Gerde's Folk City, New York, early 1960s. |

I met Bob Dylan in the Folk Center [Gerde’s] in New York. He was sitting there with his feet up on the table while we were talking to him. I knew about him because he'd just started sending the odd song to the New York Broadside, which Pete Seeger used to send to me. Bob Dylan's first songs got printed in Broadside. He said, 'I was thinking of coming to England. How would I go?' I said, 'Well, really nobody knows anything about you in England.'

Dylan was a frequent visitor to the New York Centre for Folk Music, also known as Gerde's Folk City. Davis was not totally correct in suggesting that Dylan was unknown in England, though he was not far off the mark. By December 1962 various folk music aficionados were aware of this young American, as a result of his first Columbia album released in March of that year, alongside various press reports in the folk music literature and even their own visits to the United States. Perhaps most significantly, Dylan appeared on the cover of the October-November 1962 issue of the magazine Sing Out, copies of which reached England shortly thereafter. Meanwhile, Philip Saville, upon his return to London following the initial encounter with Dylan, was able to convince the BBC to take on the American singer. He flew back to New York shortly thereafter and, following discussions with Grossman, a contract was drawn up and signed early in December. Dylan would receive his air fare to London and return, accommodation for a 3 week stay, and a £500 guineas performance fee, which, according to the American, all up cost the BBC US$2000. The plan was for filming to take place late in December, with a premiere scheduled for the following January. Dylan’s trip to London would also coincide with the Grossman-managed Odetta doing some live and television dates in London and Rome, following on her participation in the American Folk Blues Festival tour of Europe the previous October. Grossman's stable of talent at the time included not only Odetta and Dylan, but also Peter, Paul and Mary, who had a hit in July 1962 with their release of the Peter Seeger song If I had a Hammer. A number of subsequent accounts by Saville exist of his encounter with Dylan, including the following:

I was working at the BBC and one of the productions I was doing was a play by Evan Jones called Madhouse on Castle Street. It was set in a boarding house with a group of people: there was a man who locked himself in his room – he was sick of the world as it was. One of the people in the boarding house was a young poet, and a few months before I had met this young man playing the guitar with the mouth organ strapped to his mouth at Tony Pastor’s club in New York, singing these amazing songs. I said, ‘I’ve got the perfect man for this part.’ The Beeb was rather like Alice in Wonderland then. You gave them an idea and before you knew it you were on a plane, going ahead with the project. I told them, ‘There is this young man called Bobby Dylan’, and they said, ‘Well, why don’t you go out and see if he’ll do it?’ So, I went back to New York and he was still playing in Tony Pastor’s. I said, ‘Do you remember when I came along and introduced myself a little while ago?’ He said, ‘Yes.’ I said, ‘I’ve got this play.’ He said, ‘You’ll have to talk to my manager.’ I’d left him a copy of the script. I’m not sure if he actually read it or not.

|

| Bob Dylan's first album 1962 |

It is unclear whether on this second visit Saville left the copy of the script with Dylan or Grossman. Subsequent events would suggest that Dylan either did not read it before travelling to London, or, if he did, did not fully comprehend the performance expected of him. Whatever the case, the contact was signed and Dylan and Grossman made plans to fly from New York to London. Unfortunately the precise details of Dylan’s visit to England and Europe during December 1962 and January 1963 remain sketchy, despite the existence of numerous, often conflicting accounts. Whilst one of these suggests the singer flew in to London ‘mid-November’, others indicate he arrived on Sunday 16 December, Monday 17, Tuesday 18 or Friday 21, with the second last date (18 December) the most likely (Smith 2005, Harris 2008, Wikipedia 2018). Whatever the case, during his visit to London it was experiencing one of the worst winters on record, with savage snow storms blanketing the city from Boxing Day through to February 1963. Fortunately, this was weather a visiting New Yorker would not necessarily have been fazed by. Prior to coming to London, Dylan had spent time during November and early December in the recording studio, producing demos for music publisher Whitaker and writing and recording songs for his next Columbia album. His debut self-titled LP had been released to lacklustre reviews back in March 1962, though acquisition of Grossman as his new manager in August was to prove a wise career move. Grossman worked hard at achieving commercial success for his stable of clients, though a somewhat brusque manner brought him and his artists into conflict with the often Left-leaning folk music fraternity, both in America and abroad. Dylan’s second album would be released to critical acclaim in May 1963 and include songs written and performed during his European excursion. The enjoyable and energetic first album, though far from groundbreaking, would be the primary promotional tool during the London visit. Those who experienced his scattered live performances would also hear some of Dylan's new, original material. Many obviously formed a view from these that here was no ordinary folk singer, but someone very different who could - and would - ultimately take the folk-based singer-songwriter format in new directions.

|

| Autographed magazine advertisement, circa December 1962. Inscription: There are many roads to choose from. May you pick the one that will lead to answers straight and true. Bob Dylan Dec. 1962. |

Upon arrival in the wintery English metropolis mostly likely on Tuesday, 18 December 1962, Dylan was met at the airport by Saville and his then girlfriend, the artist and actress Pauline Boty (Hughes 2014). He was initially accommodated in the Mayfair Hotel near Marble Arch - a staid, upmarket establishment selected by Saville and the BBC. As the director noted:

He came over and we put him up at the Mayfair Hotel in London, which happened to be owned by a couple of friends of mine, the Danziger brothers. I took him round Carnaby Street. It was then in the full flight of London’s Sixties reverie. I remember filming him trying on all these little leather hats. He bought a couple and subsequently began to wear them in concerts. I was reasonably familiar with folk music because I met Alan Lomax when I did a production of the play Dark of the Moon for the BBC a few years before. That was all about folk music. Lomax was living in London. He was the one who, before I did Madhouse on Castle Street, really tuned me in to American folk music. He told me all about ‘Hang Down Your Head Tom Dooley’ and things like that.

Folk music historian and archivist Alan Lomax (1915-2002) was by the end of 1962 back resident in New York. He was also a friend of Dylan and a keen early supporter of the singer. The connection between Lomax and Saville, and their combined interest in folk music, would possibly have assisted Dylan in his decision to do the BBC play. Saville, in turn, was keen to take care of his charge and, like record producer John Hammond who signed Dylan up to Columbia in October 1961, could see something in the young folk singer that was different and special. Saville later noted in this regard:

He was a young man with very few words. He sort of muttered and mumbled. Until he sang, and then, of course, this astounding eloquence came rushing out. Obviously he was anarchic, but he wasn't wanting to overthrow politically. He wasn't a political animal. He wanted you to be honest, to face up to what you truly are. He had a natural nous about the rumbles in people. He used to say to me, 'You got too much intellect. You're too intellectual.' And I used to say to him, 'Well, yes, but my intellectualising keeps me in touch with what's going on.' He'd say, 'I think you should come on the road with me.' His success didn't come as any surprise to me at all. You just knew. He was like any other one-off person, you just knew. I suppose being a director - it's like water divining really. And every time you meet someone that has this, and it's not too often, I suppose it's a kind of genius - it's really being totally honest with yourself. Most people put on a face to meet other faces, so most people are walking masks. He led me to believe that it would be better to remove the mask, whatever was underneath.

---------------

3. Entering the Madhouse

When Dylan's stay at the Mayfair proved unsuitable to both its management and the singer, he transferred to the Cumberland Hotel off Piccadilly, a more accommodating, somewhat bohemian establishment which was later used by rock musicians such as Jimi Hendrix. Dylan is also known to have spent a number of nights with Saville and local musicians and casual acquaintances, as was his want during the early years in New York when he was very much the homeless wanderer. Dylan’s precise activities upon arrival in London are therefore unclear, though we do know that almost immediately he headed off to Putney for Madhouse production read throughts (Farinaccio 2007). A week of rehearsals were planned, prior to the commencement of filming. At the first of these he sat down at a long table with the director, playwright Evan Jones, a group of professional British stage and screen actors and a script. He immediately recognised Jones from his role in Fellini's La Dolce Vita (1960), a film Dylan had seen in an art house cinema in Greenwich Village (Dylan 2004). However, when it came the singer’s turn to read Lenny's lines, Saville and Jones quickly realised that Dylan would not be able to do justice to the role as written. He was no actor, and as the role included not only singing, but also a substantial amount of dialogue, all of a sudden there was a problem. Dylan himself acknowledged his inadequacies, informing Saville and Jones:

I don’t know what I’m doing here. These guys are actors. I can’t act!

|

| Bob Dylan with some of the actors from Madhouse on Castle Street. Pictured l to r: Bob Dylan, Maureen Pryor, James Mellor and Ursulla Howells. |

Saville, having provided Grossman and Dylan with a copy of the script during his visit to New York, assumed Dylan would come prepared to act out the role and perform. According to one account by Saville:

Dylan wasn’t able to deal with the dialogue at all... He asked whether he could write his own part. He was completely unable to act someone else’s dialogue. ‘Do I have to act?’ he asked me. ‘Can’t I just be a singer? Can’t I just act a couple of things?’

Dylan was being upfront, honest and showing that he was very much aware of his own talents and failings. Jones, after hasty consideration during a trip on the London underground wherein he contemplated the situation, went about splitting the part between the professional, Royal Shakespeare Company actor David Warner, who would now take on Lenny's dialogue, and Dylan as his friend and hobo minstrel Bobby, with his singing still featuring. As the actor David Warner subsequently noted:

Dylan gave the impression of being hopelessly lost. No one had the slightest idea why he had been sent there. When he started singing, it became clear.

There was therefore no doubt that Dylan's involvement would be an asset to the production. Saville later provided a more fulsome account of Dylan’s initial engagement with the play:

Bobby came to the first reading – late, in spite of us sending a car. We had the read-through of the play and everybody’s there – sound, camera, wardrobe, make-up, the odd producer. Then it came to his part and in the play Evan Jones had written these very poetic speeches about the status quo in the world, a young man beefing about inequality, et cetera. We cued him in and he just sunk down in his chair and shot his hands into his jeans and just muttered, ‘Mm … mm … mm …’ things like that. I looked at Evan Jones and I called a ten-minute break and went over to him. I said, ‘What’s the problem?’ He said, ‘I just can’t say this stuff. It’s not me.’ I said, ‘No, of course it’s not you, it’s acting.’ He was a complete greenhorn and we finally realised we had a bit of a problem. A re-cast was out of the question so we got together, Evan and I, and we came up with this idea that maybe we could make the part two parts – one was the poet and one was the musician who shared the room. When we told Bobby this, his face lit up. He said, ‘Hey, that’s great. I can scat some songs there.’ I said, ‘Yes, and you may even say a word like “hiya” or something!’ He went away a happy person.

Saville had earlier commented in regards to his impression of Dylan at the time of their working together:

He just struck me as someone who had a few things to say about the world and I loved the way he put over his songs. I thought, wouldn't it be wonderful to match this wonderful play with someone with equally extraordinary potential. I managed to convince the BBC to bring him over. When it came to reading through the play - and this character had a lot of lines, he was very anarchic - he said, 'I can't say this, I'm not an actor. All I can do is sing songs.' I thought, 'Oh great, now is the time to tell me.'

----------------

4. Blowin' in the Wind

Dylan was eventually left with a single line of dialogue and only participated in the pre-production as much as he was needed. Apart from this, he was able to check out London on foot during the day, and at night take in the local music scene. Saville

later provided a slightly different account of Dylan’s being kicked out of the Mayfair and his work on Madhouse:

Bob was staying at the Mayfair Hotel in London and he was having problems at the time with his (marijuana) smoking habit and the management of the hotel sort of lent on his manager Grossman, and indeed Bob, and asked him if he would refrain from that kind of smoking. So, I suggested to him, 'Why don’t you... Would you like to come and stay in my house and you can do what you like there', and he said 'Yeah, yeah', because he knew my wife, and he brought all his stuff and we put him in a room, in his own room, and he was happy there. Anyway, the following morning I got up to go to the toilet and I heard this music coming up - guitar sounds - and I wandered along the landing, and there at the bottom of the landing – because we had a little baby then – were two Spanish au pairs. Anyway, there he was, at the top of the stairs, singing 'How many roads must a man walk down, before you can call him a man...' These two lovely little girls were standing there, like two little robins or starlings, looking up at him. He didn’t know I was behind him – he was kind of like there - and I just applauded and just said, 'Oh Bob, would you sing that at the opening and closing of the production?' And that was before the actual song became an international hit.

A variant of the aforementioned first hearing of the song Blowin' in the Wind was also recorded:

During the time he was staying at the Mayfair Hotel he had a habit of falling asleep in the foyer and rolling a joint and smoking, fumigating the place. Finally, he was asked politely to leave the hotel. I had a house then in Hampstead, so I said, ‘Why don’t you come and stay with us, then you can live your life as you want.’ He had his guitar with him. He liked to sing some songs. At that time, I had two young au pairs from Spain and early one morning about 6.45 or seven o’clock I heard the sound of the twanging guitar. I got up, put on my dressing gown and walked along the landing and there, at the foot of the landing, were the two au pairs gazing up with their mouths open like little young birds, with Bobby, who was sitting on the staircase playing ‘Blowin’ in the Wind’. Finally, he got up and I asked, ‘Bobby, would you sing the song on the show, on the opening and closing credits?’ He said, ‘Yeah, yeah, sure.’

Of Dylan's brief stay with the Savilles at Hampstead, the director noted the following in two separate interviews:

Dylan was stoned for much of the time, the contraband most likely supplied by Grossman, and later by his friend and fellow singer Richard Farina, also in London at the time. '[Dylan's] bed times and night times and morning times were all [one] time. Late at night he would light up joints in the [Mayfair Hotel] foyer and the aromatic spread all around, and people were sniffing - 'Mmmm.... what's all that?' - and the management would come down and talk to him and they just said, 'Look, you can't do this here, it's a respectable hotel. There are clubs you can go to to actually do this.' And he said, 'Well I'm very comfortable here. I don't need to ....' and he had his feet up on the settees. Anyway, finally it was a bit of the locomotive meeting the blank wall and he just checked out. My wife then - we lived in a house in Hampstead, a large house - and she said, 'Well look, poor lad, he could stay here.' So when he heard that he said, 'Oh, can I? That would be great!' And he stayed with us. He would light up his joints and on one of the nights I found him, I think, sort of loosely hugging onto a car.

The wisdom of the decision to split the role of Lenny was reinforced by the fact that, compared to the other actors, Dylan was lax in his timekeeping, due no doubt to late nights checking out the local music and art scene, performing for friends and at various folk clubs, and writing. During his first week in London, for example, it appears that Dylan, in response to reading some of the local papers and the general post-Cuban missile crisis political atmosphere during this Cold War period, composed Masters of War.

Rehearsals rolled on and were halted as Christmas came and went. We do not know how Dylan spent those few days on either side of the holiday, though it was possibly with the Savilles or some of his new local acquaintances from the folk and art scenes, such as Martin Carthy (b.1941) and Pauline Boty (refer below). After the Christmas break, final rehearsals of the play took place on Friday 28 and Saturday 29 December. The following day, Sunday 30 December, filming took place. Unfortunately, it was brought to a premature halt at 9pm due to union restrictions. The cast and crew were forced to return to the studio on Friday 4 January to complete the filming.

Upon completion, the television production ran for approximately 60 minutes. It had been filmed using video cameras and transferred to 35mm black and white film for editing and eventual transmission. The latter occurred as part of the BBC’s Sunday Night Play series at 9 pm on 13 January 1963. It can be assumed that Dylan and Grossman watched the broadcast, though we have no record of what they thought of the final product, or if they took a copy of it with them upon their return to the United States. Only four

promotional photographs from the production have been identified, with another two also possible. The first two are very similar and feature the cast posing for the camera, with Dylan holding his guitar amidst the cast in the background and Reg Lye in the right foreground; a third is a closeup of Dylan seated and looking into the camera, with harmonica holder about his neck and a notebook in his shirt pocket; and a fourth of him similarly seated, though this time playing his guitar.

Photo #1 - Your Weekend: Sunday - Madhouse on Castle Street (refer article below).

Photo #2 - Cast publicity photograph. Source: National Film Archive.

Photo #3 - Bob Dylan on the set of Madhouse on Castle Street. Source: BBC Archive.

Photo #4 - Bob Dylan playing his guitar. Source: BBC Archive.

There is the likelihood that there was some audio editing of the footage prior to transmission, and this involved the four songs performed by Dylan. Two had originally been written by Jones, though only one was used.

The Radio Times magazine of 10 January 1963 reported on the production prior to its screening, including reproducing one of the aforementioned pictures of the cast. The article read as follows:

'I have decided to retire from the world. I shall leave your name with Mrs. Griggs, my landlady, who will notify you when I die. Please arrange for my burial, as I do not wish to trouble the occupants of the house more than is necessary.'

The ominous letter from the brother whom she has not seen for fourteen years brings Martha Tompkins to his boarding-house in Castle Street - only to find that Walter has locked himself in his room and is slowly starving himself to death. But why? Has he committed some crime? His fellow boarders, Bernard the truck driver, Lennie the student, and Bobby the guitar-playing hobo, together with Martha and two strange visitors, try to unravel Walter's secret - and in so doing find themselves revealing the secrets of their own past. The Madhouse on Castle Street is the third play for BBC-TV by Evan Jones, following The Widows of Jaffa and In a Backward Country. His film scripts include The Damned, which has yet to be released, and Eve, which stars the outstanding French actress Jeanne Moreau in her first English-speaking part. In Philip Saville's production, Martha Tompkins is played by Ursula Howells, while Maureen Pryor is cast at Mrs. Griggs the landlady and James Mellor as Bernard. Appearing as Bobby the hobo is Bob Dylan, brought over from America especially to play the part. Only twenty-one, he is already a major new figure in folk-music, with a reputation as one of the most compelling blues singers ever recorded. The song for which he is best known is 'Talkin' New York,' about his first visit to the city in 1961. A skilled guitarist, his special kind of haunting music forms an integral part of tonight's strange play.

--------------------------------

The televised play received a mixed reception when it went to air on the evening of 13 January 1963. The reviewer for the Western Daily Mail was 'baffled' by Jones's play (Smith 2005). The Times review of 14 January was less critical, placing the work and Saville’s direction in the context of the evolution of drama presentations on British television:

Bold Camera Work and a Savage Setting

It is tempting to look carefully at the first major BBC television drama production after the official arrival of a new head of drama to see whether it foreshadows anything exciting and new. Whether or not The Madhouse at Castle Street last night does represent the first fruits of Mr. Sydney Newman’s rule, it was certainly very different from the usual run of BBC productions. For one thing, the director, Philip Saville, is a graduate of Armchair Theatre, and his production had all the characteristics of his most boldly imaginative work for that series: the rich chiaroscuro, the intricate camera movement (rather more roughly executed than usual), the passion for vast, meaningful close-ups. The production also had one or two more startling touches, particularly in the brief, vividly odd New Wavy flashbacks in which suddenly we see what the characters are really thinking, not what they happen to be saying at the time. All this was fascinating, and it was not, as has sometimes been the case with Mr. Saville’s work, beside the point of the play. Mr. Jones’s play is a strange, freewheeling piece about a man who has said goodbye to the world and has simply shut himself up in his room. No, that is not quite it; it is about the people around him, and their various attitudes toward him: the motherly, easy-going landlady, the three peculiar fellow lodgers, the sister who has not seen him for 14 years, the girl with whom he used to have luncheon, the clergyman full of reach-me-down psychology. When the hermit finally comes out he at once decides, quite rightly, that they all want to eat him alive, and he goes straight back, this time for keeps. It is a strange, savage, unpredictable world Mr. Jones conjures up, and Mr. Saville, with the aid of an excellent cast (Miss Maureen Pryor and Miss Ursula Howells were particularly good) and some haunting songs by Mr. Bob Dylan, brought it powerfully to light.

--------------------------------

The Listener magazine also reviewed the program, noting in regards to Dylan’s performance that he 'sat around playing and singing attractively, if a little incomprehensively' (Harper 2012). A viewer remembered the following in regards to the program as screened:

I saw this when I was about ten or eleven, in a little coal mine town in Wales. My parents had read something about the program and decided to watch it. It made enough of an impression to remain with me in fragments. I had no idea who Dylan was. I remember him sitting on a doorstep or by a wall or something as the action went on in the foreground, and at some point he sang with the camera close on him. He was wearing his peaked cap. I don't even remember, or don't even know if I understood the story of the play. The main story perhaps could be that David Warner would not come out of a room. Dylan would sing, and this man would not come out of a room. The BBC wiped away so many things in its treasure trove. Now it’s just fragments in most people's memories.

It is likely that Dylan appeared throughout the production in the background, with the camera focusing in on him through closeups whenever he sang, though there was also interjecting dialogue. He most likely featured in the presentation of Blowin' in the Wind at the beginning and end of the production. Another original viewer noted:

I remember watching Madhouse as a 13-year-old. All my family were disgusted with Bobby's 'singing'; it was then that I thought, "Well, if nobody else likes it, it must be good!" Needless to say, I became a huge fan.

The playwright Evan Jones later made the following remarks in regards to Dylan and the broadcast:

He was clearly a fish out of water and completely unsuited to the drama and to everyone else! But he had a tremendous sense of self-reliance, and we had to find a way to use him... It worked a treat. I don't think I was at too many rehearsals after that. I finally saw the first run through of the play, which begins with "Blowin' in the Wind". It was absolutely mind-blowing. Spine-chilling.

Local folk singer Martin Carthy was critical of the final production, noting in one interview:

I was very puzzled. I didn’t really make anything of it. I think I was more excited that my mate was in it than anything else. A lot of people were very confused by it. It got stinking reviews.

Of Dylan’s performance, Carthy observed that he was 'absolutely deadpan' throughout, even though, as a 'mischievous bugger', he had rewritten some of the songs, injecting sardonic humour into the lyrics of, for example, Jones' Ballad of the Gliding Swan. The deadpan nature of Dylan's performance is perhaps reflected in the March 1964 Canadian Broadcasting Commission production The Times They Are a-Changin' whereby he performs in a doss house (see below). Carthy also attended the filming of Madhouse when it was unexpectedly cut short:

I think we were on the (studio) floor, and the play was just going along, and they were just doing it, and then suddenly it wasn’t happening anymore, and people were running around saying 'They've pulled the plug. They've pulled the plug.'

Unfortunately, no modern assessment can be made of the finished play as the original footage - apparently both the original video and the 35mm presentation copy - was destroyed by the BBC in 1968 as part of their wiping and reuse of tape program (Rossen 2017). No copy is known to exist, despite a subsequent world-wide search (Wall 2005). Annotated copies of the script survive in the Evan Jones Archive housed in the Bodelian Library at the University of Oxford. They were placed there following the writer’s death in 2011. All that survives of Dylan’s performance, apart from the aforementioned photographs, are three rough audio recordings taken off-air by members of the public during the one and only broadcast. They comprise all or part of the four songs he sang – (1) Blowing in the Wind, (2) Ballad of the Gliding Swan, (3) Hang Me, Oh Hang Me and (4) Cuckoo Bird - along with some incidental music. Off-air recordings were made at the time by schoolboy Pete Read and older music fans Hans Fried and Ray Jenkins. Read’s tape includes parts of (1) and (2); the Jenkins tape is similar to Read’s but also includes (3); whilst the Fried tape includes parts of (3) and (4). The quality varies from barely audible to clear. The following is a concise list of the extant recordings, as released on a fan-produced bootleg CD during January 2006:

| |

| Rooftop, New York, 1962. |

SOURCE ONE - "recording A" - the oldest circulating version

1. Blowin' in the Wind [1:45]

2. The Ballad of the Gliding Swan [1:50]

SOURCE TWO - "recording A" - a new transfer from the oldest circulating version source tape - more natural than the previous one, but also showing some bad ageing of the master tape. Received August 2005 and possibly done in relation to the ongoing BBC research for the documentary on the play.

3. Blowin' in the Wind [1:46]

4. The Ballad of the Gliding Swan [0:43]

SOURCE THREE - "recording A" (well remastered, or "recording b") - mainly excerpts from the 2005 BBC4 documentary entitled

5. Blowin' in the Wind (harp) [0:14]

6. The Ballad of the Gliding Swan [0:20]

7. Blowin' in the Wind (harp) [0:14]

8. The Ballad of the Gliding Swan (echoed) [0:13]

SOURCE FOUR - "recording B" - a 4-song tape - includes excerpts from

9. The Ballad of the Gliding Swan [0:51]

10. Blowin' in the Wind (harp) [0:13]

11. The Coo Coo Song [0:30]

12. The Ballad of the Gliding Swan (w/voiceover + lyrics read out) [2:36]

13. I Been All Around the World (Hang Me Oh Hang Me) [0:28]

14. Blowin' in the Wind [0:51]

15. The Ballad of the Gliding Swan (complete w/voiceover) [2:17]

16. Blowin' in the Wind (harp) [0:15]

SOURCE FIVE - "recording C" - this (reportedly 4-song tape) was discovered too late to be included within the BBC4 documentary main section, but some fragments were used while the credits rolled.

17. The Ballad of the Gliding Swan [0:59]

18. Blowin' in the Wind [1:49]

A BBC representative noted the following in 2005, at the time of the initial search for the lost footage and in regards to the final production of the play:

The drama itself was very Pinteresque, like many programmes popular at the time. Millions of people would tune in and then wonder what it was all about at the bus stop the next day. Dylan, perhaps not surprisingly, played a folk singer who spent most of his time sat on a flight of stairs. . . and commented on the ongoing action through songs and dialogue. I think Dylan expected to have a much larger part but I think he could not handle the dialogue. It is my understanding that this was the very first time he sang Blowin' in the Wind on television.

Dylan had written the famous song back in April 1962, and this was indeed its first public television broadcast. Its significance was noted by the BBC representative:

It was an experience that his peers wouldn't have enjoyed. The Wednesday and Sunday night plays on the BBC were unique to British culture, and they had an effect on a whole generation of songwriters coming through, like Lennon and McCartney and Ray Davies. Madhouse is a brilliant study of alienation, and I'm sure that it must have fed into the imagination of this restless young Bob Dylan too. But it wasn't just Dylan's appearance. The play itself seems to me to be truly significant, and not only that but David Warner was at the height of his fame in 1968. Someone must have realised its importance by then - a year of change and revolution. To have junked the recording in 1963 might have been a mistake, but to do so five years later strikes me as verging on the sinister.

Judging by subsequent appearances on television through to 1965, Dylan was happy with his presentation in Madhouse. Upon his return to the United States he made a number of extended television appearances. For example, he sang Blowin' in the Wind, Man of Constant Sorrow and Ballad of Hollis Brown on the Westinghouse TV special, broadcast on 3 March 1963, less than two months after the screening of Madhouse on British television.

Bob Dylan, Blowing in the Wind, Live on TV, March 1963. Duration: 2.35 minutes.

Bob Dylan, Westinghouse TV special [extract], 1963. Duration: 4.57 minutes. Song: Ballad of Hollis Brown. Backed by a banjo.

Perhaps the most skillfully done of these early television performances is within the March 1964 Canadian CBC production The Times They Are a-Changin', which was part of the Quest documentary series. Within that 30-minute-long program, which features Dylan as the sole artist, he is seen singing to a group of destitute men (actors) relaxing as they smoke, eat and play cards in a studio set up to represent a large room in a boarding house. The scenario had obvious similarities with Madhouse on Castle Street and represents a homage to the songs and style of Woody Guthrie and folk singers of that era. Dylan’s confident presentation therein is perhaps built upon his experience gained at the BBC just over a year earlier.

Bob Dylan, The Times They Are a-Changin', Live on TV, Canadian Broadcasting Commission, March 1964. Duration: 27.19 minutes.

Both the Westinghouse and CBC shows reveal elements of what would have been seen in the Madhouse presentation. Whilst that process occupied Dylan on and off between his arrival in London and through to 4 January 1963, he was also able to occupy himself with a variety of social activities, related to both music and also to simply having a good time and getting to know the city of London, a place he had previously sung about visiting and which obviously drew his interest.

-------------------

5. Bobby and Pauline

| |

| Pauline Boty, London, circa 1962. |

None of the accounts of Dylan’s visit to London given by Philip Saville or the various members of the folk scene he met with mention Pauline Boty. Saville’s stunningly beautiful girlfriend at the time was said to have picked Dylan up at the airport, along with Saville, accompanied him around town, introduced him to various art galleries and entertainment venues, and accommodated him at her flat for four days (Smith 2006). Boty was one of the founders of British Pop art and featured in the March 1962 Ken Russell BBC documentary Pop Goes the Easel.

It has also been suggested that Dylan's song about a 'gal so fair' written in January 1963 just prior to his departure from London, was based on his relationship with Boty. Whether she was the model for Liverpool Gal, or it was one of her friends, will probably never be known, such is the mystery which surrounds many of Dylan’s works, his personal relationships, and the disconnect between events of his life and his prose. Ever the escapist, and despite this subterfuge, Dylan has stated that if you want to know about his life, look to his songs. In this way he has been able to deflect questions on his many private liaisons, especially whilst on the road.

Pauline Boty was a vivacious personality - an artist, actress and performer who was in a relationship with Saville at the time of the visit, though it has also been noted that she was very much a free spirit in regards to her sexuality, as was Saville. Nothing much is known of Dylan’s relationship with Boty, though the words of Liverpool Gal, if they indeed refer to her or one of her friends, suggest something intimate. They also flesh out some of the feelings and events Dylan experienced upon his arrival in London, with the song apparently written in the same plaintive, romantic vein as John Lennon’s Norwegian Wood from 1965. Dylan's words perhaps reflect his feelings and actions arising out of separation from his girlfriend Suze Rotolo:

When first I came to London town

A stranger I did come

I'd walk the streets so silently

I did not know no-one

I was thinking thoughts and dreaming dreams

The kind when you roll along

But most of all I was thinking about

the land I'd left back home.

I’d stand by the river Themes

with the wind blowing through my hair.

And who should come and stand by me

but a London gal so fair.

Her eyes were blue, her hair was brown

Her face was gentle and kind

For a second, well, I clear forgot

The land I left behind.

As we began walking and talkin’

All through the English air

I did not know where we'd end up

‘til we came to the top of a stair.

As we lay round on a worn-out rug

the room it was so cold

And we talked for hours by the inside fire

‘bout the outside world so old.

All through our sweet conversation

She thought my ways were so strange

But I know there was one thing about me

That she would try to change

And the night passed on with the drizzling rain

There's one thing I found out

[A pair of sweet curls] I know too well,

Her love I know not much about.

And I awoke the next morning

And the rain had turned to snow

I looked out of her window

And I knew that I must go

I did not know how to tell her

I didn't know if I could

But she smiled a smile I'd never seen

To say she understood.

And thinking of her as I stood in the snow

How strange she appeared to be,

On the reason I was leaving,

she seemed no better than me.

I gazed all up at her window

where the snowy snow-flakes blowed

I put my hands in my pockets

And I walked 'long down the road.

So it’s now I’m leaving London, boys

Well, the town I'll soon forget,

Likewise its winds and weather

Likewise some people I met

But there's one thing that’s for certain

Sure as the sunshine down

I’ll never forget that Liverpool Gal

Who lived in London Town.

The song was only sung once - on 17 July 1963 when Dylan visited a friend, David Whitaker, in Minneapolis. It is possible that some of Dylan’s unaccounted days in London were spent with Pauline and her female friends, especially prior to the New Year. It is also likely that Boty's relationship with Saville - which was then on the wane - plus Dylan’s own wavering relationship with Suze Rotolo, meant that this aspect of Boty's life was generally hidden from notice. What is known is that, apparently on the first day in town, Philip and Pauline picked Dylan up at the airport, dropped him off at the Mayfair Hotel and later took him to a supper party at the flat of Boty’s friend and fellow artist Jane Percival (Tate 2013). The latter later recalled:

They turned up with some musician in tow, and Pauline said, “Look, I’m terribly sorry, Jane, we can’t come in, we’ve got to go to a reception, but will you look after this guy for the evening? He’s over to do a play for Philip.”

Percival went on to note that Dylan sat in the corner and played songs during the party, including Blowin in the Wind. He then spent the night with another artist, Joanna Carrington, who lived downstairs, and returned the next morning to say farewell to Percival.

|

| Joanna Carrington |

|

| Joanna Carrington in her studio 1963. |

|

| Joanna Carrington painting in her Notting Hill studio, 30 April 1963. Photographer: Larry Ellis, Daily Express. |

Carrington, a painter of landscapes and interiors during this period, had a solo show at the gallery in the Establishment club during 1962 (Mason 2005). Saville later noted that Dylan ‘spent a lot of time at art galleries’ during the visit, and it is likely that Boty facilitated this, along with acquaintances such as Carrington (Chambers 2011). Whatever the truth, the visiting singer’s involvement with women during his time in London would remain private and mysterious. He engagement with the local folk scene was not so difficult to pin down.

-------------------

6. The London Folk Scene

From the day he arrived at the Mayfair, Bob Dylan almost immediately set out to engage with the local folk music scene. He would do in London what he had been doing in New York since arriving there in January 1961, namely: refine his craft as singer, songwriter, musician and performer; develop a collection of friends and mentors / supporters; and build a repertoire of songs and stories, based on the folk tradition, but ultimately presented in his own unique style. By the end of 1962 he was therefore looking to expand his horizons further and the trip to London would be a way of achieving that, given the often deep connections between the British and American folk traditions. He had been given a note of introduction by Pete Seeger to his sister Peggy, a fellow musician who moved to England in 1956 and was now the partner of the influential folk musician Ewan MacColl (1915-1989). Seeger also suggested he contact local event manager Anthea Joseph (1924-1981). Venues that Dylan is known to have performed at, or visited in order to observe the local players and just enjoy himself, included the following:

The King and Queen pub. A Friday night folk club in a small, upstairs room of a pub. Dylan performed here at least twice and possibly visited at other times. He also met Martin Carthy here.

The Singers Club, previously known as The Ballads & Blues Club, at the Pindar of Wakefield pub. A Saturday night folk venue managed by husband and wife team Peggy Seeger and Ewan MacColl. Dylan is known to have appeared twice at this staunchly Left – wing venue. Seeger and MacColl were less than hospitable to the young American.

The Troubadour, Old Brompton Road, Earls Court. A Saturday (late) and Tuesday night folk club that accommodated approximately 100 people and was managed by Anthea Joseph. Dylan visited the club on a number of occasions in December and January.

Bunjies Coffee House and Folk Cellar at 27 Litchfield Street. Folk cafe.

The Establishment. A comedy and jazz club set up in 1962 by Peter Cook. It is possible that he visited here with Pauline Boty.

The Roundhouse pub on the corner of Wardour and Brewer Streets, London. This was formerly a jazz and blues venue; however, Bob Davenport ran a monthly folk night in a first-floor room there in 1962. Apparently, Dylan was kicked out.

Peanuts folk club, King’s Arms, Bishopsgate / Sir Paul Pindar pub, Thursday nights.

Surbiton and Kingston Folk Club. Dylan listened to a performance by Carolyn Hester and Dick Farina.

The Blue Angel, a men’s club. Apparently Dylan performed here and noted the presence of author Robert Graves.

The Black Horse.

Many of these visits took place between rehearsals and filming of Madhouse, though most appear to have been weekend events. The folk scene was just a small part of the London music landscape at the time, with blues and jazz featuring, amidst a vibrant pop and rock 'n roll scene which saw the arrival of The Beatles with the release of Love Me Do in October 1962. Though there were similarities between the New York / Greenwich Village and London folk scenes at the time, there were also differences, and Dylan was keen to learn as much as he could during his short visit, especially as many of the so-called 'traditional' American folk songs had their roots in the British Isles. Groups such as The Weavers – featuring Pete Seeger - and the Irish Clancy Brothers were prominent on the American folk scene during the late 1950s and early 1960s, drawing much of their music from the British tradition. Dylan was friends with both Seeger and Liam Clancy during his time in New York. Peggy Seeger subsequently noted the comparatively different scenes in the context of Dylan’s visit:

What might have puzzled Dylan was the non-nightclub atmosphere the folk clubs had [in London]. There were no lights, there were no microphones ... there was no ritualised nightlife to it. It was a bunch of ordinary people coming to their pub. (Smith 2015)

The British scene was in many ways communal, amateur and pub-based, rather than professional and club-based as in the United States. The London folk scene was, at the end of 1962, still largely run by fans and players, with few performers having managers. Whilst it was in many ways factional, it was small enough for the major players at the time to perform on a regular basis at a core group of clubs such as the King and Queen, the Singers Club and the Troubadour. Prior to arriving in London, Dylan had spent almost two years working the New York folk scene, becoming an experienced, confident performer. He therefore found the visit engaging, stimulating and fun as he studied the local players and their repertoire whilst also, on occasion, letting his hair down, as any 21-year-old is want to do during the festive season.

----------------

7. Natasha Remembers

An interesting assessment of the then male-dominated London folk scene in the early 1960s comes from a young, 16 year old fan at the time by the name of Natasha Morgan. Natasha was excited by Dylan when he first appeared at venues such as the Singers Club, to such an extent that she clearly remembered the feeling when interviewed in 2008, some 46 years later:

I was just 16-17 years old then and I was having to work really quite hard to get my parents to let me go and I was surrounded by these really sleazy men who would be trying to get me to drink beer, which I didn't like. They all wanted to sort of snug or have me sit next to them. And it was quite unpleasant in some ways. And then they would sing these songs that were quite racey. I can look at those photographs and I can see, you know, that I am gobsmacked. My eyes are absolutely on him and I'm in awe. I'm so thrilled. It's so alive what he's singing, how he is. He looks like the kids I went to school with. He doesn't look like he's going to take advantage of me. He's not threatening. He's not sleazy. He's not even unhealthy, or if he's unhealthy it's in a really attractive way.

[Of Dylan's original songs and his manner of presentation she made the following comments: It was not about old men taking advantage of pretty young girls and getting them in the family way and, you know, all that sort of thing. It was completely different. It was talking directly to my generation. Even the young folk singers that were there - some of whom I knew - were doing their own versions of the old songs, so that there was something that was really quite nostalgic about it, whereas there was nothing nostalgic about Dylan.

This is a significant comment as it ties Dylan in with his own generation, and the young people of the time who were open to new music and not bound to the past. It also highlights the strikingly contemporary elements of his songwriting and developing repertoire, which was not just a rehash of traditional songs and tunes, or purely political. Dylan was covering a wide variety of forms and topics, making it difficult for the establishment to pin him down, though widening his fan base considerably in the process.

-----------------

8. Martin Carthy

Far from being a shrinking violet in regards to the somewhat closed shop he was faced with in London, Dylan showed bravado in taking each and every opportunity on offer to engage with the local folk scene, though it needs to be said that many of the venues were open to visiting Americans and up and coming locals. Dylan noted the results of this engagement with locals in a 1984 Rolling Stone interview with Kurt Loder:

I ran into some people in England who really knew those [traditional English] songs - Martin Carthy, another guy named [Bob] Davenport. Martin Carthy's incredible. I learned a lot of stuff from Martin. (Loder 1984)

From Carthy, for example, Dylan learnt two songs - Scarborough Fair and Lady Franklin’s Lament, which he later adapted the tunes of for his own new works, including Girl of the North Country and Bob Dylan’s Dream, both of which featured on his next record. He is also known to have learnt Dominic Behan's The Patriot Game from Scottish folksinger Nigel Denver, using it for his own With God on Our Side. Dylan’s ability to adopt and adapt traditional forms to create new, original and popular music was both applauded and denounced by his fellow folk musicians at the time. He would face similar hostility when he went electric in 1965. One young folk singer who supported what he did and befriended the visiting American was Martin Carthy. Dylan and Carthy spent time together throughout the visit, and their initial meeting was fortuitous. It most likely occurred on the day of Dylan’s arrival in the country, or shortly thereafter on Friday, 21 December, though one account has been published which begins his English adventure on the 18th (Heylin 2011).

|

| Sing Out! magazine, Oct-Nov 1962. |

Dylan was not completely unknown to the English at the time of his arrival in London, despite what Tony Davis had told him. His first album had been released there the previous March, though it apparently had little impact at the time, comprising, as it did, mostly covers. Importantly, the latest issue of American folk music magazine Sing Out! Appeared in London during November and featured Dylan on the cover, along with an article and accompanying lyrics from three of his songs, including Song for Woody and Blowin' in the Wind. The Sing Out! issue suggested a songwriter on the rise, and this promise would be revealed with Dylan’s next album. Ewan MacColl and Peggy Seeger had also encountered Dylan as a young folk fan in 1960 during a concert tour of the States. At the time he was a distinct nuisance, pestering MacColl for an autograph. The encounter was therefore not an endearing one for the brusque English folksinger. As Peggy Seeger remembered in regards to her first meeting with Dylan in London:

For many of those local folkies in the know, Dylan’s arrival in town was of interest; for the majority of those in the clubs it would be their initial encounter; and for some, such as Carthy, it left a distinct impression. Martin Carthy was born in 1941, the same year as Dylan, and just 3 days earlier. He subsequently provided a number of important accounts of Dylan’s London visit and his own encounters with the American. These were supplemented by numerous incidental accounts from a variety of sources and individuals. Unfortunately, many of these do not correlate or provide precise detail in regard to when and where specific events took place. Perhaps this confusion is a result of the festive season, the widespread use on the scene of drugs such as alcohol and marijuana, and the fact that Dylan was yet to break internationally and was, as such, a minor player and perhaps forgettable to many. He also, at times, maintained a low profile during the London visit. Nevertheless we can glean a lot about his engagement with the fold scene from subsequently published first hand accounts. * The King and Queen Martin Carthy was one of the locals who saw something special in Dylan and remembered the first time the singer and songwriter came to his notice:

One day in '62 I went into Collett’s bookshop on New Oxford Street and they had a new copy of Sing Out! And on the front was a picture of this bloke, Bob Dylan. A great fuss was being made about him and they printed his song 'Blowin' in the Wind'. There was this wonderful article about him – how he was the heir to Woody Guthrie and he’s spent time with Woody Guthrie and gone to visit him in hospital. Then about three weeks later I was singing with the Thameside Four one Friday night at the King and Queen, back of Goode Street, and who should walk in the door but the cover of Sing Out! I sang a couple of songs and walked over and I said, 'You're Bob Dylan, aren't you?' He said, 'Hey.' I said, "I saw your picture on the front of Sing Out!' He said, 'Oh yeah?' I said, 'Would you like to sing a couple of songs?' He said, 'Ask me later.' I went back and Marion Grey, one of the Thameside Four, said to me, 'Is he going to sing?' I said that he'd said to ask him later, so we got up and sang a couple of songs and as I finished I looked towards him and he just gave this ever so slight nod. I said, 'Do you want to do it now?' He said, 'Yeah.' So I introduced him as the bloke on the current cover of Sing Out! and he came up and he sang. He was electrifying. He was brilliant. He always sang these funny ragtimey songs. Jack Elliott's was 'San Francisco Bay Blues' and he had one similar to that. Then he did a talking blues - 'Talking John Birch.' I can't remember what the third song was but he took the place apart. It was an L-shaped room and we sang from the corner. There would be a hundred there at the most, probably eighty. He was very, very good indeed. Afterwards we talked a lot and I said, 'Are you going to come to the Troubadour tomorrow?' He said, 'What's the Troubadour?' I told him and he said, 'Oh, Albert's told me about that place, maybe I'll come.' This was his manager, Albert Grossman. And the next night he came down to the Troubadour. He came to the King and Queen every week and the Thameside Four had a gig at the Troubadour on the Tuesday. Then I would sing at the Troubadour on Saturday. And he came to all of those and sang. Different stuff every time - he never sang the same song twice. He sang things like 'The Death of Emmett Till' and at the Troubadour he sang that wonderful one to the tune of 'Pretty Polly' - 'Hollis Brown.' I'll never forget the night he sang 'A Hard Rain's Gonna Fall', because he started - 'Where have you been my blue-eyed son / where have you been my handsome young one' and I'm thinking, 'Oh, he's going to sing Lord Russell [Randal].' But that line was where the similarity with Lord Russell [Randal] ended. He just took off on this great song, 'Hard Rain.' And in 1962 that was revolutionary. (Bean 2014)

|

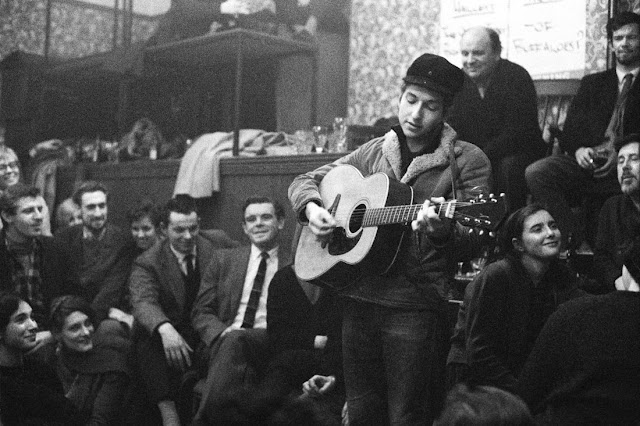

| Bob Dylan, King & Queen, 21 December 1962 |

Another early account by Carthy was contained in an interview with David Brazier on 26 September 1991. It begins with his encounter with the Sing Out cover:

Martin Carthy: I saw his picture on the front of Sing Out!, whenever the hell that was (November 1962). I suppose it was sometime in 1962 when they printed "Song for Woody" and "Blowing in The Wind." But there was also an interview with him and they were all very excited about him. And just a few weeks later I saw him sitting in the audience in the King & Queen. There were very few clubs in London at that time and visiting Americans used to just make a bee line for the few ones there were and, you know, anything that was loosely folky. And one of the clubs was a club I used... I used to be in a group called The Thameside Four - in the days when there were groups, not bands. The Thameside Four ran a club at this pub called the King & Queen, behind Goodge Street station, next to the Middlesex Hospital, and I saw this bloke sitting in the audience and I recognised him, and I went up to him in the interval and I said, "Excuse me, your name is Bob Dylan, isn't it?'' He looked up and he said, "Yes'' and I said, "Do you fancy singing?" and he said "No'' and I said ''Oh, all right'' and he said, "Well, maybe I will later on; ask me later." So, l said "OK.'' We got up in the second half and sang a few songs and (then) I sang a couple of songs and I just looked across and nodded and he just nodded, like that, nodded his head, and I called him up, gave him an introduction and said I'd seen a couple of his songs printed and they looked really nice songs and this was him and he stood up and sang. As far as I know that was the first time he sang in England. He asked about other places to go, and I told him there was The Troubadour on a Saturday and a Tuesday night. We were involved in both of those - at The Troubadour on a Saturday night, I was basically their resident at that time and The Thameside Four had a night at the Troubadour on Tuesday, and he came along to both of those. He also went to Bunjies, I think, and he went to the Singers' Club and sang there. I don't remember when it was, maybe the Saturday following that Friday when I saw him at the King & Queen or perhaps the following Saturday. When he stood up and started to perform at the King & Queen, it was just... the audience knew they were watching something that was really good. Anybody who says anything different, that the audience didn't like him, is talking through their hat. The audience loved him. He did three songs and they demanded an encore. He was great, very funny and very dry. He spoke a little to the audience, not a lot, just a little, but then he never did talk to the audience that much. I remember seeing him at the Royal Festival Hall (17 May 1964) about 18 months afterwards when he did his solo concert there and he was astounding. He was astounding. He didn't talk at first, and then he started telling everybody... he told the audience the plot of the movie "Hootenanny," which is all about muscle men and bikini-clad young lasses all cavorting about singing folk, singing "hootenanny" music... but that was later on. In 1962, he was making this play and it was winter; it was pretty cold.

DB: Dylan based some of his songs on things he'd learned from you -- "Girl From the North Country," for example, came from your "Scarborough Fair." Did he tell you at the time that that's what he was aiming at doing?

MC: Oh yes. He would always ask me to sing it, that one and Lord Franklin. And when he came back from... erm, I thought he went to Portugal but somebody told me he went to Italy, but anyway he went away, because there was a screw up with the filming on The Madhouse on Castle Street, a strike, actually. At nine o'clock the technicians pulled the plugs and because they hadn't finished filming, they had to start all over again. So, he went away for a while and then came back and filmed it again. And when he came back, he'd written Girl From the North Country, he came down to The Troubadour and said, "Hey, here's Scarborough Fair" and he started playing this thing. And he kept getting the giggles, all the time he was doing it. It was very funny. I think he sang about three or four verses and then he went. ''Ah man ah,'' and he burst out laughing and sang something else. So yeah, l knew what he was doing. It was delightful, lovely, 'cos I mean he... he made a new song. DB: It's part of the folk tradition, isn't it, to base one song on another song? MC: Well, I don't know whether it is a folk tradition or not, but I took it as an enormous compliment, to the song and, if you like, to me. You know, I thought he was a tremendously honourable bloke. Still do. It was a great thing to have done. DB: Do you think there was a big difference in Bob between '62 and '65 or was it just that the people around him were different? MC: Huge, huge, huge difference. His coming to England had an enormous impact on his music, and yet nobody's ever said it properly. He came and he learned. When he sat in all those folk clubs in '62, he was just soaking stuff up all the time. He heard Louis Killen, he heard Nigel Denver, he heard Bob Davenport, he heard me, he heard The Thameside Four, dozens of people. Anybody who came into The Troubadour, or came into the King & Queen, or the Singers' Club, and he listened and he just gobbled stuff up. The first complete album he made after he first visited England was The Times They Are a-Changin', and England is all over that album; it's all over Another Side of Bob Dylan too and it's all over a large area of his work at that time. All those tunes he wrote sounded English, Irish, Scottish, you know, a particular kind of highly melodic tune. He stopped playing sort of raggy tunes, and blues - he went back to those later on, when he went back more into rock 'n roll. But he was forever changing things around; he still is. He turns old songs upside down. (Carthy and Brazier 1991)This interview is supplemented by another extensive one which covers the London episode and the contemporary English folk scene in depth (Carthy 2013). Carthy notes therein some of the positive response Dylan received, alongside the negative reception encountered from individuals and groups such as hard Left Communist Party folkies including MacColl and Seeger.

|

| Martin Carthy, King & Queen pub, ? 21 December 1962. |

|

| Martin Carthy, King & Queen pub, ? 21 December 1962. |

|

|

Carthy’s comments regarding MacColl are reinforced by Dylan’s in a 2011 interview:

I thought he was dead. So many people are like him, man, the

things that MacColl has said about Tom Paxton and Phil Ochs are downright

nasty, just worthless, and obvious – yeah, it's very limited. Traditional folk

music in America is great music, and it's so criminal the way people want to

stick it in a little bottle, with water in it, and keep it in a swamp." (Shelton 2011)

In

1979 New York folk musician Eric von Schmidt (1931-2007) noted

the following in regards to Dylan and his persona at the time of the London

visit:

We played at some folk club one night and heard a good singer and

guitar player, Martin Carthy, do a folk song called "The Franklin." It

was about a boat that explored Antarctica or something. It was a totally lovely

song. Dylan got Martin to show him all the chords and put the melody right in

that amazing head of his. Next record he puts out there is "As I was

riding on a western train..." [sic] Dylan was really amazing back then

[Jan 1963]. He kept changing sizes. He changed shape from day to day. On

Tuesday he'd be big and husky; on Wednesday he'd be this frail little wisp of a

thing; on Friday he'd be some other size and shape. The trickiest part was that

he was always wearing the same clothes. (Schmidt and Rooney 1979)

In

another account, Carthy described the first meeting at the King and Queen as

follows:

There was a regular Friday night folk club upstairs at the pub and I remember, while I was singing a song, there was this guy - who I’d seen on the cover of some magazines - sitting near the front of the audience. I finished a couple of songs, walked over to him and said, ‘You’re Bob Dylan’! (BBC 2005) \

He then noted how he talked Dylan into getting up and singing three songs:

He had fabulous presence and a great sense of comedy. (BBC 2005)

Professional

photographer Brian Shuel was at the gig and took a number of shots of this first English performance. He also photographed Dylan at the Singers Club shortly thereafter.

When Dylan turned up in the King and Queen, Martin Carthy and Nigel Denver and the Thameside Four were doing a gig there. Alison, who's now my wife, was on the gate and I was chatting her up outside and this kid in cowboy boots came upstairs carrying a guitar. He said, 'Is this a folk club?' I said, 'Yes. Are you gonna sing?' Because usually, if you were going to sing, you didn't pay. So I took him in and sat him in the back row and I introduced him to Martin. Nigel was singing and at the interval Martin hadn't asked him and Dylan came over to me. He said, 'Can I talk to you about folk music?' I said, 'Yes, down the stairs, in the loo.' In those days we couldn't afford a drink in the pub. We used to smuggle half-bottles in, half-bottles of whiskey, and you went down to the loo in the interval. We went down and he was shaking. I had to hold him by the shoulders. I don't know if it was the pot. It wasn't fear, he was just jiggling. I offered him a drink and we talked about music. I told him there's all rebel music in Scotland, even the farmers' songs. And he asked me if I was Hamish Henderson. Another question he asked me: 'Does Ewan MacColl live in a slum?' After that conversation we went back up and Martin asked him on. He did a couple of Guthrie songs. After people like Alex Campbell, who knew Guthrie's material, this young kid with a mouth organ - it was just a very kind of wishy-washy imitation. Martin asked him back that night, and at the house that he asked him back to, in Hampstead, Martin and his wife Dorothy lived in one room, Peter Stanley the banjo player lived in another room and Nigel and I had another room.

I was there that night as my mate Nigel Denver was doing a spot,

as were the Thames Side Four, and my future wife, Alison Chapman McLean, the

photographer, was on the door. I didn't recognise Dylan, but when he came in

with his guitar and I asked him if he wanted to sing, he declined and sat near

the back. I mentioned to Martin Carthy that an American kid with a guitar had

come in and perhaps he should ask him to sing, which he did. Dylan and I had a

chat in the interval, downstairs in the toilet, where I offered to share my

half bottle of whisky with him and Nigel, but he declined. We talked about a

few things and he asked me if I was Hamish Henderson (Nigel had been singing

some of my songs). I was hovering at the door that night as I was 'courting'

and preferred my future wife's company to the singing, so I witnessed Bob

coming in. (Cossar 2017)

Following closing time at 11pm, Dylan struck up a conversation with Carthy and expressed a keen interest in exploring the local scene:

Well he said, 'What else is going on?' and I told him about the

various other clubs. 'There's the Singers Club in Soho Square and that’s a

Saturday night club, and there's The Troubadour in Earl's Court and that’s a late-night

club starting about 10.30.' And he took it all in. After the club he came back

to ours and my wife Dorothy said, 'I'll put the kettle on. Make a fire Mart.' So,

I said, 'OK.' We had this useless piano and a samurai sword and we had to keep

warm. So, I went and dragged a bit of the piano and got the sword and as I was

about to swing the first one he stood in front of me and said, 'You can’t do

that – that’s a musical instrument!' I said, ‘It's a piece of shit!' And I

started chopping it and I felt this little bit of a shadow at my shoulder and I

looked around and he said, 'Can I have a go?' So, we built a fire. (Carthy 2013)

Dylan

would develop a comradery with Carthy over the following weeks, visiting clubs, watching performances, and learning songs off him. Another local performer who encountered Dylan at various folk clubs was Louis Killen:

At the King and Queen I was just sitting in the audience. The singers tended to go to as many club as were there because this was what we were devoting our lives to. Those who were professional did, and I had become professional by then. A lot of my time was spent in London so I would go to all the clubs within reach. [Dylan] came to the Troubadour. Martin was living with his first wife up in Hampstead. I remember on a couple of nights us all being in there after the club, swapping songs and what have you. Bob asked me to sing again and again 'The Leaving of London.' And, of course, it was out on his next record as 'Farewell', difference set of words but same tune. He didn't mention my name. Somebody wrote in the English Folk Dance and Song Society magazine that Bob Dylan got 'The Leaving of London' from Nigel Denver. Nigel didn't even sing that song, it wasn't in his repertory, not in those days. (Bean 2014)

He wrote 'Farewell' .... He took 'Scarborough Fair' and he took from 'Lord Franklin' - 'Bob Dylan's Dream' - and he did that song of Louis and he learned songs from Bob Davenport. Nigel Denver's big party piece at the time was 'Kishmul's Gallery' - he wrote an amazing song around 'Kishmul's Gallery'. He'd get really excited about hearing a song and then go home and write something about it or around what he remembered. He did that all the time. We had a flat in Belsize Park. He came back after that Saturday night at the Troubadour, the second night he was here. We laid a fire .... settled down .... drank lots of tea ... just talked about music and played to each other - doing what twenty-one-, twenty-two-year-olds do.

* The Singers Club

Following